I. The Locality. Mozyr is located in the deep Palesse. Palesse occupies a vast area: it encompasses most of the Pinsk district, part of the Bobruysk and Rechitsa districts, part of the Ovruch district in Volyn Province, and part of the Radomyshl district in Kiev Province, but the center of Palesse is the Mozyr district.

According to ancient accounts, this entire huge area was once flooded by waters, forming one continuous lake connected by one of its channels to the Baltic Sea. At present, most of this area is covered with sands, swamps, lakes, forests, and shrubs. From the lakes and swamps of Palesse flow many streams, creeks, and rivers, the main one of which, into which all the others flow, is the Pripyat River. It flows through the middle of Palesse, constituting a natural and the most convenient route of communication for the inhabitants of Palesse, both among themselves and with the rest of the world. Besides this route, others are very inconvenient, and in the spring, when the rivers and lakes overflow their banks and the swamps fill with water, they become impossible. There is very little land suitable for settlement in the Mozyr district, which is why the population is not numerous. In many places, over a vast distance, no human habitation is visible, only here and there stands a lonely fisherman’s hutshack or a half-ruined Jewish inn (korehma).

However, in the absence of man, millions of other lives fill the vast area: the lakes and rivers teem with many kinds of fish, the swamps sway with an uncountable number of bitterns, throughout the Pripyat Marshes, and especially near the swamps, uncountable hordes of various insects swarm in the air, the forests and swamps are nesting grounds for a multitude of birds of all kinds, and there too, various animals find a cozy refuge and tempting prey: hares, martens, foxes, beavers, badgers, wolves, elks, wild boars, and bears;

there are also plenty of shrews, moles, grass snakes, lizards, and various kinds of snakes, including venomous ones. This land is primitive in many respects. It should be noted, however, that the primeval forests are thinning out more and more year by year due to the activity of industrialists, and with the emancipation of the peasants, the population began to increase; lonely farmsteads are growing with new houses, and large villages are spawning new settlements on newly formed wastelands.

The population is almost entirely of the Orthodox faith; only near Mozyr are there outskirts with a Roman Catholic population. Civilization has yet to barely touch the Pripet Marshes: people live and work there as their grandfathers and great-grandfathers lived. The main occupation of the population is agriculture, and in some places also fishing, while all crafts, not to mention trade, are in the hands of the Jews.

The district town of Mozyr is located at the edge of the district, almost on the border with the Rechitsa district, and is situated on the right bank of the Pripyat River(1).

(1) The name Pripyat is derived from 3 multiplied by 5, i.e., that 15 different rivers flow into it. The Pripyat originates from lakes and swamps near the town of Shatsk, Volyn Province; it flows through the Mozyr district, part of the Rechitsa and Radomyshl districts of Kiev Province, and below the town of Chernobyl flows into the Dnieper.

The river is navigable; steamers, berlinkas (a type of barge), barges, and rafts carrying ship timber, construction wood, firewood, various wooden products, stone, resin, and tar travel down it to Kiev. From there, bread, salt, and other vital products are delivered to the Polesia region. In spring, the Pripyat floods, especially where its banks are low, over a vast area of 2 to 9 versts, but in dry summer, communication on it is interrupted due to numerous shoals and sunken logs (koldy).

The town is stretched along the river; on the other side, it is surrounded by mountains, among which there is a small hollow that forms the market square, and its continuation between the mountains forms the Svidovskaya or Pokrovskaya Street. On the outskirts of the town, there are two ravines: the Rosomaksky, near the cathedral, and the Pyatnitsky, near the Paraskevnevskaya Church. Mozyr is located 360 versts from the provincial city of Minsk, and 230 versts from Chernigov and Zhitomir.

A postal road from Bobruysk to Zhitomir passes through it, as does the once-main Belarusian tract, which was lined with birch trees by order of Empress Catherine II and is now being mercilessly destroyed by the peasants. Mozyr’s most convenient connection is with Kiev via the Pripyat River, which flows into the Dnieper, especially now that a weekly passenger service has been opened from Kiev to Pinsk via Mozyr. Although this service is sometimes interrupted due to shallow water, it is only for a very short time. Therefore, both in ancient times and today, Mozyr has a very lively connection with Kiev via water communication in all respects. Around Mozyr, there are various hills and burial mounds; one that particularly draws attention is a hill located near Mozyr, among the mountains, rising in the shape of a cone, called the “Shatersky.”

These hills are the result of various battles, so not rarely occurring in ancient times near Mozyr; here fought Russians against Lithuanians, Lithuanians against Tatars, and Cossacks and Haidamaks against Poles. For example: in 1205, the Lithuanians attacked Russian principalities and plundered Russian churches and monasteries until they were defeated near Mozyr by the Severian princes, the Olgovichi, who received Mozyr, Slutsk, and further regions as an appanage. So too, Erdivil, the first of the Lithuanian princes, defeated the Tatars near Mozyr and put their prince, Boydan, to flight. Besides this, folk tradition points to many mounds as legacies of the Swedish and [1812] Patriotic wars. In 1812, General Ertel’s corps was stationed in Mozyr.

When Mozyr was founded is unknown, but based on historical data, it can reliably be counted among the oldest cities of the Minsk province. In deep antiquity, it apparently belonged to the Grand Principality of Kiev. In 1155, Grand Prince Yuri Vladimirovich Dolgoruky gave Mozyr to his ally, Prince Svyatoslav Olgovich of Chernigov. In 1157, after the death of Dolgoruky, when Izyaslav Davidovich, Prince of Chernigov, ascended the Kievan throne, Svyatoslav moved from Mozyr back to Chernigov, giving Mozyr to Grand Prince Izyaslav Davidovich. And so Mozyr again passed to the Grand Principality of Kiev, but it seems that at times Mozyr was united with Kiev under one prince, and at other times it became a separate appanage principality, perhaps also because the Grand Princes of Kiev gave Mozyr together with Turov as an appanage to their sons and relatives, but who the princes of Mozyr were, there is no information. In 1227, according to Polish historians, Mozyr already belonged to the Lithuanians. In 1240-41, Mozyr was ravaged by the Tatars; in 1497, the Tatars ravaged the environs of Mozyr, during which the Metropolitan of Kiev, Makarii, was killed near the town of Skrigalov. He was traveling to collect donations for the restoration in Kiev of the ancient St. Sophia Cathedral, which had been destroyed by the Tatars; his relics rest in the Kiev-Sophia Cathedral. After the union of Lithuania with Poland, Mozyr fell under Polish rule. The unfavorable conditions in which Mozyr was placed, for example: the scarcity of natural gifts and the various battles that occurred around it, certainly could not contribute to its prosperity.

Christianity spread in Mozyr, if not during the time of St. Vladimir, then during the reign of his immediate successors. The following circumstances lead one to assume this: Christianity initially began to spread from Kiev along waterways, and Mozyr was connected to Kiev by such a route. If one believes local tradition that St. Vladimir himself planted Christianity in Turov, established an episcopal see there during his reign, and also founded the B. Leshchinsky Monastery in Pinsk, which stands on the Pina River flowing into the Pripyat, then in all likelihood, he also laid the foundation for Christianity in Mozyr.

And by the 11th century, Christianity had already spread so much in the Mozyr district that in this century, an episcopal see undoubtedly already existed in Turov, located on the Pripyat, 70 versts upstream from Mozyr. In the 12th century, there already existed two monasteries in Mozyr: the men’s Petro-Pavlovsky and the women’s Paraskevievsky. Unfortunately, no written records have survived from these monasteries, as from many others that existed in the Minsk eparchy. According to the oral tradition of some, the Petro-Pavlovsky Monastery was located where the Markman houses now stand, built on land that belonged to the Sukhovshchyna Basilians, and now [belongs] to the Sukhovshchyna church of the Rechitsa district; the khutor (farmstead) Yasnaya Gora also belonged to it. Others, however, say that the monastery was located outside the city on Yasnaya Gora (Clear Hill). Here is the information found about these monasteries by the compiler of the Historical-Statistical Description of the Minsk Eparchy, Archpriest Nicholas. In 1401, Feodor Kolodka, a voevoda (military governor), gave the Mozyr monks 100 nevozai (?) on condition that the Petropavlovskaya Church be built at the foot of the hill. In 1602, the Mozyr Yasnogorodsky Abbot Methodius Svochkevich and the brethren exchanged the Tyrkovsky court with Ivan Sadlovsky for the khutor Mikhnovsky. The name of this abbot was recorded in the Synodikon of the Slutsk Holy Trinity Monastery. During the Cossack wars with the Poles, this monastery was destroyed. Its land was seized by the Sukhovshchyna Basilians.

Its known abbots are:

- 1642, Abbot Methodius Svochkevich.

- 1753, Senior Hieromonk Theodosius Zenevich.

The Mozyr Paraskevievsky Women’s Monastery. No written records have survived about this monastery either. This monastery was located where the Pyatnitskaya Church now stands, which in later times most likely also served as the monastery church. The landowners of the Sadlelnik estate, located 7 versts from Mozyr, attribute the foundation of this monastery to the ancestors of their family(2).

(2) According to the story of the deceased landowner Adolf Obukhovich (who converted to Orthodoxy in 1863 in the Pyatnitskaya Church, as pobuilt by his ancestors) their family name was not Obukhovichi but Obukhovy, and they were Orthodox; the ancestors of Obukhovich owned many lands in Kiev, the last of which were sold by them recently. From their ancestor Andrei Obukhov, the Kiev Brotherhood Monastery acquired the Sverchkovskoye town property and hayfields on Obolon (Kiev with its other school, Askochensky Vol. 1, p. 61). According to his story, the Obukhovichi built churches in the Paraskevievsky Monastery, in the village of Grabov in Mozyr district, and in Sidelniki, the remains of which exist to this day.

After the transition to the Unia, and then to Catholicism, of the monastery’s benefactors — the Obukhovichi, Lenkevichi, Osverki, Prozory, and other wealthy families, now landowners of the Mozyr and Rechitsa districts — this monastery fell into such poverty at the beginning of the 18th century that the nuns of this monastery mortgaged a voloka of land to the nobleman Oppoka for 400 zlotys to repair their church. Around 1720, it belonged to the Bragin-Selets Monastery. Around 1793, the majority of this monastery’s land was owned by the szlachta (nobility).

Its known abbesses are:

- 1704, Abbess Seraphima (of the [unclear] monastery).

- 1726, Abbess Alexandra Kulevskaya (of Selets and Mozyr).

The following monasteries also existed in ancient times in the Mozyr district:

- The Turov Borisoglebsky Men’s Monastery.

- The Turov Varvara Women’s Monastery.

- The Morochansky Monastery, formerly St. Nicholas, later the Dormition Men’s Monastery.

4. Monastyryuk, or the Ogolintsy Hermitage, near the townlet of Petrikov.

There were also quite a few parish churches in the city of Mozyr. According to the clergy register of 1896, there were still 5 parish churches in Mozyr. There is no doubt that there were more; some of them were taken by the Catholics. The existence of Polish settlements (Gvardiyevka, Kozevyki, Drozdy, etc.) amidst the solidly Orthodox population of Mozyr townsfolk, and the fact that not all townsfolk in the city itself are of the Orthodox faith—there are also Catholics—forces one to think so. It is precisely against such violence from the Catholics that the Mozyr Archpriest Leonty Savitsky complained in 1747 to the Slutsk Archimandrite Iosif Oransky, stating that in his district, only 7 out of 50 churches remained, all the others having been seized by the Uniates. Of course, this refers to churches in the povet (district) as well. In the city itself, Catholicism met strong resistance from the Orthodox, who, exhausted in an unequal struggle, turned to the Cossacks for help and themselves participated together with them in many wars against the Poles. This is why, under the Treaty of Zboriv, the townsfolk of Mozyr, who had suffered more than others, received back their former rights and liberties, which had been granted to them by the Polish government to attract them to the Unia.

To judge the degree of zeal for Orthodoxy among the residents of Mozyr and the lively connection that existed between Mozyr and Kiev, as the center of Orthodoxy, we consider it appropriate to point here to the example of the Mozyr resident Anna Gulevich, who in the time of disaster for the Kiev-Bratsky school (which is now the academy) proved to be its great benefactress. In 1604, at the request of the Kievan Metropolitan Hypatius Potii, by a Royal decree, a whole part of Kiev-Podil, where the closest brethren of the Epiphany School lived, was given to the Catholic Bishop of Kiev, who lost no time in oppressing both the brethren and the school itself. Dominicans and Jesuits, competing with each other, established their schools here to bring the hated Epiphany School into decline. To make matters worse, a fire in 1614 destroyed both the Epiphany Church and the school itself. There were no means to restore both the church and the school; the Jesuits, of course, rejoiced at such a helpless situation. At this time, the wife of the Mozyr marshal Stefan Lozka, née Gulevich (1), by a deed recorded in the acts of the Kievan land court in 1615, with the consent of her husband, donated and bequeathed in perpetual ownership her hereditary estates, enjoying noble rights and privileges, for a monastery of patriarchal stauropegion, for a school for children of both noble and burgher origin, and furthermore for an inn for spiritual wanderers of the Eastern Catholic faith. The noble benefactress of the Kievan school, in her deed, also explains the reason that prompted her to such a donation: “Living,” she says, “constantly in the ancient holy Orthodox faith of the Eastern Church, burning with pious zeal for the spread of God’s glory, out of love and attachment to my brethren—the Russian people, and for the salvation of my soul, I have long intended to do good for the Church of God” by this deed, Gulevich bequeathed her own courtyard and land in Kiev, located within known boundaries, with all the appurtenances and incomes relating to that courtyard and land. On the basis of this deed of gift, they immediately proceeded to build a house and a school with a house church attached to it.

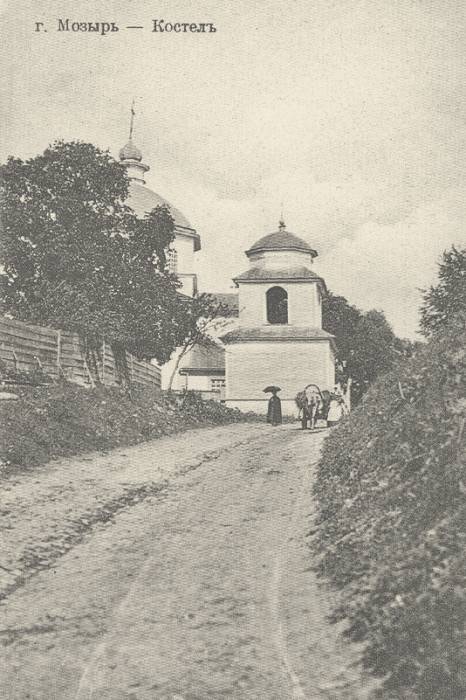

But despite the opposition of the Orthodox, Catholicism, patronized by the Polish government and thanks to the tireless and treacherous activity of the Jesuits—among whom Andrzej Bobola and Martin Tyrovsky are especially well-known—became established in Mozyr. In the middle of the 17th century, the Jesuits established a school with a church (kościół) here, which they brought to a flourishing state; here the children of all the noble families of the Mozyr, Rechitsa, Bobruysk, and Ovruch districts were educated. Then a fara (i.e., a parish church) was built, which still exists today; at the end of the 17th century, a Bernardine monastery was erected near the parish church, founded mainly by the landowners Oskorki, formerly Orthodox; and a little further away, a female Mariavite monastery; at the beginning of the 18th century, two Cistercian monasteries, male and female, were built in the suburb of the city, Kimbrovka. Of these monasteries, the Bernardine and Mariavite were closed in 1831 due to political affairs, and the male Cistercian monastery was in 1864. At the present time, there exist two churches (kościoły) in Mozyr: the Parish church and the female Cistercian monastery.

The goal of the Jesuits, although not fully, was achieved: all that was intelligent, all that studied in the Jesuit schools, converted to Catholicism or became Polonized. It is true that few apostates from the faith of their fathers were found among the townsfolk (meshchane), but those who remained, due to their poverty, were unable to maintain their Orthodox churches, some of which fell into disrepair, while others were destroyed by fires at various times.

After the third partition of Poland in 1793, Mozyr became part of the newly formed Minsk Eparchy. The present Mozyr district, with part of the churches of the Rechitsa district nearest to Mozyr (e.g., Borbarevo, Narovaya, Demidovichi, and others), was divided into four deaneries (protopopii). At the time of the formation of the Minsk Eparchy in 1794, these deaneries contained the following number of churches: Mozyrskaya – 12, Turovskaya – 8, Davidgorodetskaya – 11, and Petrikovskaya – 6.

Prior to the formation of the Minsk Eparchy, clergy for the aforementioned churches were ordained by the Kiev Metropolitan, and some of the priests even studied at the Kiev Academy.

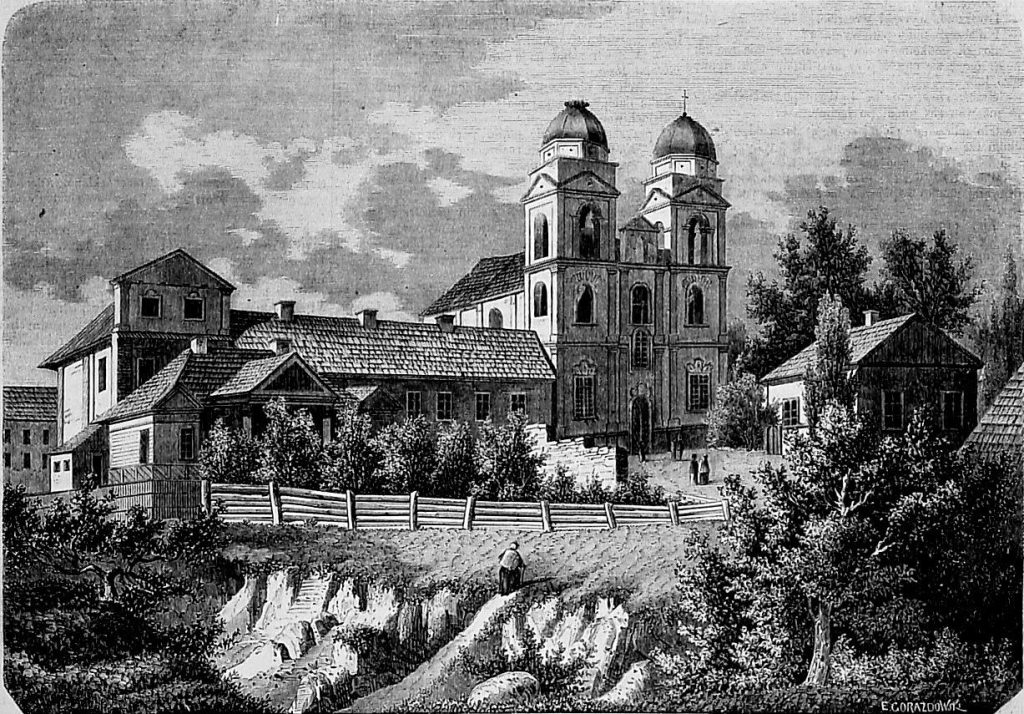

In 1796, as seen from clergy registers (klirovye vedomosti), the following churches existed in Mozyr: St. Michael’s, St. Nicholas’s, the Holy Savior’s (Spasskaya), the Nativity of the Theotokos (Rozhdestvo-Bogorodichnaya), and St. Paraskeva’s (Paraskevievskaya). Among them, the church in the name of the Holy Archangel Michael was considered the cathedral. But by 1861, there were only 2 parish churches: St. Nicholas’s, which replaced the cathedral, and St. Paraskeva’s. All the others were destroyed by fires: St. Michael’s, St. Nicholas’s, and the Holy Savior’s in 1809, and the Nativity of the Theotokos in 1839. In the 1820s, through the efforts of the church and parishioners, a St. Michael’s Church was built, which burned down again in 1839, and the remaining meager its property was transferred to the newly built, makeshift St. Nicholas Parish Church, constructed somehow by the parishioners, which is extremely unseemly both in its external appearance and internal condition (!). In 1851, an estimate was drawn up for the conversion into a cathedral of the Bernardine church (kościół) abolished in 1831, but work on this construction barely began in 1864. To familiarize ourselves with the history of the construction of the present cathedral, we consider it appropriate to cite here the petition from the clergy and parishioners of the Mozyr Cathedral, submitted by them, with the blessing of the former Archbishop Michael, to the Holy Synod in 1863.

Here it is:

“The residents of the city of Mozyr, Minsk Eparchy, humbly petition, and their request consists of the following points:

- “In the city of Mozyr, after the burning down of the St. Michael’s Cathedral Church in 1839, there is not a single more or less decent Orthodox church, so that we, living in a land very scarce in natural gifts, surrounded by various circumstances of life unfavorable to Orthodoxy, although we live in a land Orthodox since ancient times, in the ancient Turov Eparchy, where back in the 12th century the illustrious St. Cyril, Bishop of Turov, so gloriously labored—a figure famous in the History of the Russian Church—we do not even have that consolation in our life to be able to pray to the Lord God in a fitting temple. Hence, we can say, Orthodoxy is visibly declining in our land, and with it, Russian national identity. The late Emperor Nicholas I of blessed memory ordered to hand over for the Orthodox-for an Orthodox cathedral the building of the abolished Bernardine monastery, and the Holy Synod issued an order to draw up an estimate for the conversion of this building into an Orthodox church. Based on this estimate, drawn up back in 1851, 11,570 rubles and 96½ kopecks were allocated. Although the Bernardine church (kościół), after its destruction by fire in 1839, was roofed twice—once at the expense of the church and once at the expense of the parishioners—however, due to the height of this building, neither a wooden nor a thatched roof could hold, and therefore damages occurred in the said building that were not indicated in the estimate; hence, no contractor, for the allocated sum, expressed a desire to undertake the work.

In 1860, instead of 11,570 rubles 96½ kopecks, 14,289 rubles and 63 kopecks were allocated for the said reconstruction, but again no one expressed a desire to undertake the reconstruction, partly for political reasons (since the Roman Catholics are petitioning for the return of this building to them), and partly because new damages, not indicated in the estimate, have occurred in the Bernardine building, which remains without any roof, windows, or doors. Therefore, there is no hope that the said works could be carried out by contract. Meanwhile, the building of the Bernardine church, having been left for 23 years without any repairs, and for many years having had no roof, windows, or doors, suffers significant damage each year, and the vaults of this once magnificent building may soon collapse. And then it is unlikely that anything can be made of it, and we will lose hope of ever having a decent Orthodox temple. Based on all of the above, we most humbly request:- That it be ordered to carry out the conversion of the Bernardine building into an Orthodox cathedral by the economic method [direct administration], under the supervision of the local Diocesan Authority, with the release of the sum required for this, according to the present cost of works and materials, and demanded that this reconstruction be carried out so that the sum allocated for the said reconstruction be released to the district treasury and issued in parts to the committee with the permission of the diocesan authorities, etc.”

The Holy Synod, heeding this petition, released the sum specified in the estimate, amounting to 14,289 rubles and 63 kopecks, and entrusted the Minsk diocesan authorities to immediately commence the construction of the cathedral in Mozyr, either by contract or through an economic committee. Fortunately, in the person of the Minsk merchant A. A. Svechnikov, a well-known builder of churches in the Minsk eparchy at that time, a contractor was found for the construction of the Mozyr Cathedral. The diocesan authorities, having concluded a contract with Svechnikov, formed an economic committee to supervise the work. Thus, at the beginning of 1864, the construction of the cathedral commenced. However, the sum released was only for the construction of the cathedral and its iconostasis, while nothing was allocated for the acquisition of bells, vestments, utensils, and for roofing the residential building adjacent to the church, which stood almost entirely without a roof. Under these circumstances, the economic committee turned with a request to the former chief of the Northwestern Territory, Count M. N. Muravyov, and with an appeal for donations for the benefit of the cathedral to the Moscow newspaper “Den” (The Day). The unforgettable chief of the N.W. Territory released 2 thousand rubles at the disposal of the committee, and through the editorial office of the newspaper “Den”, various donations from Moscow and St. Petersburg were received, and in money and in kind. Significant donations were received from Princess Elizaveta Dolgorukova, Countess Varvara Protasova, F. M. Sukhotin, Lyamin, and many others. And in the person of the Moscow priest Sergei Dmitrievich Tsvetkov, the Mozyr Cathedral acquired for itself such a benefactor, through whose mediation many donations in kind were received from Moscow, and through whom bells and all church utensils were acquired for the cathedral at a reduced price. Donations also came from local residents. All these donations, together with the 2 thousand [rubles] released by order of the Chief of the Northwestern Territory, gave the committee the opportunity to acquire five bells for the church, church utensils, some sacristy items, to install an iron roof on the residential building, and a fence around the church. The contractor A. A. Svechnikov, in gratitude to the committee for its labors in rebuilding the cathedral, donated five large icons, copies of icons from the Minsk Cathedral, hanging in the high place (gornoe mesto) and in the middle of the church on four pillars, conceded about 500 rubles for the installation of the iron roof on the residential building, arranged a warm church in the side chapel, and donated altar and analogion vestments. In 1865, the stone three-altared cathedral was finally brought into splendid appearance and was consecrated in the same year, on September 5th, by the former Archbishop of Minsk, Mikhail. The main altar was consecrated in the name of the Holy Archangel Michael, the right side chapel (warm) in the name of St. Cyril, Bishop of Turov, and the left one was not consecrated; its altar is intended for the sacristy.To understand the state of Orthodoxy at this time, we consider it appropriate to cite here the word (sermon) spoken at the consecration of the cathedral by the former rector of the cathedral, P. G. T.